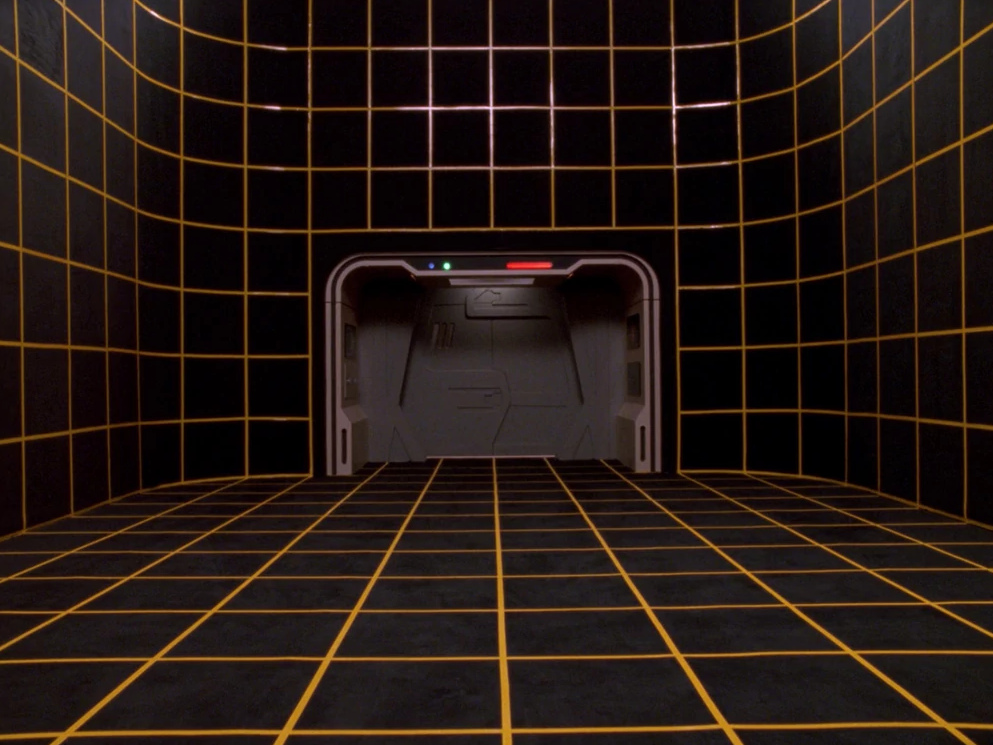

In your book, Are You Dreaming?, you mention that you became a big fan of the television series, Star Trek: The Next Generation. At some point, you realized lucid dreaming seemed akin to the ‘holodeck’ or virtual reality room on the Enterprise. How did you play with this idea in your teenage lucid dreams?

In reality it was a very simple premise. I believe I was in my mid-teens and during that time I was struggling a little with mastering a more direct and reliable form of dream control. Whilst during the vast majority of my lucid dreams I was more than able to steer the dream in the direction I wished, often the more direct aspects of dream control, such as rapid changes in locality, or conjuring people or items, remained somewhat more elusive; a little more unreliable than was satisfactory.

I understood the basic role of expectation in such endeavours but had yet to find a method that gave consistent results. It was during this period where I noticed the similarities between the lucid dreaming experience and the fictional holodeck.

I understood the basic role of expectation in such endeavours but had yet to find a method that gave consistent results. It was during this period where I noticed the similarities between the lucid dreaming experience and the fictional holodeck.

Fortunately, as those who are familiar with the show will understand, the virtual world of the holodeck was voice activated; a character need only speak a command along the lines of ‘Computer, pause time’, or ‘Computer, generate a Hawaiian beach,’ for the holodeck to respond accordingly. The simple logical step was to approach lucid dream control in the same manner and fortunately it worked wonderfully.

Now, as readers of my book will understand, the premise behind this particular form of dream control is not the means of control itself (the vocal commands) but the genuine belief and expectation that such a method will be successful. I call this technique ‘reframing’, as essentially the principle is to reframe the underlying belief in how the dream world operates in such a way to convince yourself that such a feat is possible; fictional worlds and modern day computer interfaces offer us creative options for reframing a dream‘s control system.

Because my teenage mind, rather nerdily, wholeheartedly bought into the Star Trek universe, it was a very small step for my mind to accept the premise of the lucid dream as a kind of holodeck. This reframing increased my expectation for success and as such the world of dreams responded positively to this increased expectation and confidence. My book Are You Dreaming? explores the principles of reframing in far more detail and of course isn‘t limited to forcing your dreams to involve body hugging starship uniforms! Reframing is a powerful, versatile and simple technique and is a stepping stone towards truly understanding the deeper principles behind expectation and dream control.

Many of us have noted the analogy of lucid dreaming as akin to an inner ‘holodeck’. Though a simple analogy, does it really hold true? Or asked another way, how does a lucid dream differ from a holodeck?

Of course it is the nature of analogies to only take us so far. Eventually the similarities will break down. In the case of the holodeck, it‘s certainly far from a perfect match. The most obvious difference between the experience of dreaming and that of any external virtual reality, is the self-generated nature of dreaming.

Our dreams are a deeply interactive process far beyond the obvious manipulations of a virtual body on a virtual world. In a computerised virtual world one is interacting in a very simple almost crass manner, in a series of ‘physical‘ movements and commands etc., aping our most basic waking interactions with the physical world. The dream world, being a construct of the mind, is a much more subtle web of interaction.

Both the dream world and our persona within that world are products of the same organ, namely the human brain. In dreams there is no distinction between external and internal, as essentially everything occurring inside a dream is occurring within the mind. Therefore, in a very real sense, every thought, emotion, distraction or psychological experience within a dream is an interaction with the illusory external environment, more specifically, it is the environment.

The emotion of joy you may experience as you look over a beautiful dreamscape, genuinely influences that vision and it becomes a form of feedback loop. Your enjoyment of the beauty feeds and manipulates the vision of the beauty and vice versa.

The emotion of joy you may experience as you look over a beautiful dreamscape, genuinely influences that vision and it becomes a form of feedback loop. Your enjoyment of the beauty feeds and manipulates the vision of the beauty and vice versa.

Furthermore, in a computerised virtual world you would experience a world designed and imagined by another; it would therefore lack the intense immediacy and connection one has with one’s own mental models. To put this into a simple example, the ‘monster’ you may experience in a virtual world, would be the invention of someone else – sure it may be frightening, but how much more terrifying a beast could your own mind devise, having access to your most deep and personal primal fears?

A dream, unlike any other virtual experience, is a rollercoaster ride through your own psyche, only you are not simply experiencing the ride, you are the ride. You are both the experiencer and the experience. It‘s a fascinating concept and one that, I believe, can lead you down a philosophical rabbit hole into entirely new ways of thinking and help you develop a new respect for what it means to be human.

In your book, you state that Frederik van Eeden did not coin the term, lucid dreaming. If not van Eeden, then who created the term? Do you think van Eeden borrowed it from them, or simply happened upon a similar expression?

That‘s correct. The original use of the term lucid dreaming, as we know it today, was coined by MarieJean-Léon Lecoq, better known by his title Marquis d‘Hervey de Saint-Denys, in his 1867 work, Les rêves et les moyens de les diriger; observations pratiques (Dreams and the means to direct them, practical observations). The only available English translation of this work comes from Morton Schatzman, published in 1982 (now out of print). The translation is incomplete and lacking large portions of the original text. It has also lost much of the mood and the beautifully colourful writing style of the original.

To compound and confuse matters, Schatzman‘s accompanying notes are somewhat misleading and it is in these notes that Schatzman comes to the erroneous conclusion that Saint-Denys use of ‘rêves lucide’ has a different meaning to how we would use it today, which is demonstrably wrong.

Indeed, the first use of the term lucid dream can be found on page 287 of Les Rêves, in the sentence: ‘C’est-à-dire le premier rêve lucide au milieu duquel je possédais bien le sentiment de ma situation’ (transl.: That is to say, the first lucid dream in which I had the sensation of my situation). This makes the term ‘lucid dream’ a ripe 147 years old.

As Shatzman‘s translation is the only English translation available, scholars and dream researchers have often assumed his interpretation was correct and as such, a kind of ‘chinese whispers‘ occurred, in which this one misinterpretation has been restated in all the major texts on lucid dreaming ever since.

As for van Eeden, it‘s clear in his work, A Study of Dreams (1913), in which he classified seven types of dream, including the lucid dream, that he was very much aware of the work of Saint-Denys. Indeed he even mentions both him and his book within the text. So, I feel it‘s very safe to say that van Eeden borrowed the term, or at the absolute least, he must have picked it up subconsciously after studying the work of SaintDenys (I‘d say the former is the most likely explanation).

Plus let us not forget that the word lucid is somewhat vague and perhaps not one that that would naturally jump to mind, so the chances of both picking it by chance are slim at best. Also the fact that van Eeden‘s text was more widely available after being popularized by Charles Tart in 1969, will have also played a role in this blurring of the true origin of the term. I feel, once we look at the evidence, it‘s clear that Saint-Denys coined the term, to then be borrowed later by van Eeden.

Whilst it may seem like a trivial point to some, I feel it‘s important for us as a community of dreamers to be aware of our roots, and Saint-Denys was a truly wonderful and insightful chap. It‘s only right that he be given the credit he deserves.

As you report, St-Denys enjoyed performing experiments in lucid dreams. Tell us briefly about one of his lucid dream experiments. Why do you think most lucid dreamers seem unaware of his work?

One of my favourite of his experiments – mostly because it‘s such a great example of his thinking and a nice glimpse into his human side (I have the inclination he was somewhat of a ladies man) – is one in which he had built a music box that played two particular tunes. This music box was designed to be played whilst he was dreaming and to hopefully influence them.

Now, it would seem, there were two ladies whom SaintDenys wished to dream about, and so to create a connection between these women and each tune, he paid a bandmaster to play these tunes whenever he danced with either of them.

The implications of this are somewhat self evident: develop a connection between a piece of music and a person during his waking hours, then to play these tunes whilst he slept in order to conjure the woman into his dream. He reports that the experiment was a success, although the account of the dreams in question don‘t offer much detail as to how the dreams then progressed.

Several of his experiments were along these lines: create a unique association during waking hours, then to use that association to influence the content of his dreams. All very ahead of his time, especially considering that only recently with the advent of devices such as the Nova Dreamer and the DreamSpeaker are we finally catching up with his way of thinking.

As for why most lucid dreamers are unaware of his work, well, sadly, as I‘ve covered earlier, this is mostly due to the blurring of his place in lucid dream history and perhaps more importantly the fact that his book has remained stubbornly unavailable in a comprehensive, accurate and complete English translation.

In France and other areas of Europe, Saint-Denys is far more highly regarded and respected amongst lucid dreamers. However, I have good news on this front, I am currently working in conjunction with a skilled translator and other experts to finally bring the first full English translation of Saint-Denys work to light. I‘ll be making a full announcement on this project in the near future (so for those interested, join me on twitter and facebook to stay up to date).

I am very pleased and proud to be able to instigate this project and feel that it will hugely benefit us all as lucid dreamers. However, we‘ll almost certainly need the help of the lucid dream community, so once the project is ready to set sail, I‘ll be very thankful for the support and backing of other lucid dreamers. It‘s a genuine chance to really be part of something wonderful.

Also, it seems that you created a technique about ten years ago, called the Cycle Adjustment Technique. Can you briefly talk a bit about that? (I urge interested readers to purchase a copy of your book to see these techniques described in greater detail.)

Has it really been ten years already? How quickly time passes! Although in reality, the idea is considerably older than ten years. Well, as you say, probably the best explanation of the technique can be found in the book, so I‘ll not belabour the point too much here. Essentially the CAT method is a behavioural approach to inducing lucid dreams, aiming more towards the biology of awareness rather than the psychological approach favoured by most lucid dream techniques.

It can be thought of as a natural alternative to using supplements such as galantamine; a way to biologically prep your mind in such a way to improve the chances of awareness and therefore lucidity.

Through a regimented series of tweaks to ones sleeping cycle, the method aims to activate the chemistry of critical thinking during the final REM phase of a night‘s sleep. I stumbled upon the idea quite some time ago, by pure serendipity, back during my college days. By chance my lecture schedule was on an alternating pattern, giving me this cyclical routine of waking early one day, then sleeping in the next and so the pattern would repeat. I noticed that on the days I slept in, the occurrence of lucidity was much greater.

This idea must have rattled around my mind for some time, as many years later and after a lot of experimentation and thought, I eventually managed to fine tune this idea and establish a pattern that seemed to greatly increase the chances of lucidity and a reasoning behind why this occurred. I‘ll not share the specific details of the method here, but you can find the full and detailed version in my book, or alternatively variations based on the original idea shared online, back in 2004, can be easily found on most popular lucid dreaming websites.

On your website, you state, “In addition to his role as an oneirologist, Daniel is also a trained magician, specialising in the field of psychological illusion (also known as mentalism). Through studying and working as a psychological magician, Daniel has developed an understanding of the nature and limitations of human awareness. He has found a strong crossover between the magical deceptions that can be performed on the waking mind, with those that arise in the dream state.”

This comes across in your writing as both observant but somewhat skeptical. Fair enough. So in your book, you mention lucid dreams in which the deceased appear. And you mention the lucid dream of Gennadius, as told by St. Augustine. So, do you mean to tell us that all lucid encounters with the deceased serve as merely ‘beautiful gifts’ from the subconscious?